A Constant Battle

Friday, 24 October

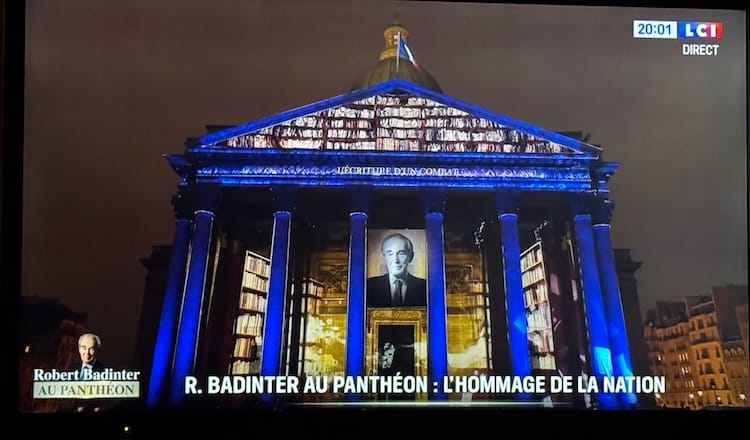

On my way home from lunch with a friend the other day, my bike-lane was blocked by a large cordoned off area around the Pantheon. From the elaborate sound and light systems being installed…

…you’d have thought they were preparing for a rock concert. In fact, the lawyer-politician Robert Badinter, who died last year just short of his 96th birthday, was being inducted into the Republic's sanctuary for famous French men (75) and women (five) that evening. Minister of Justice under President François Mitterrand, he was best known as author of the law abolishing the death penalty in France exactly 44 years earlier on October 9th 1981.

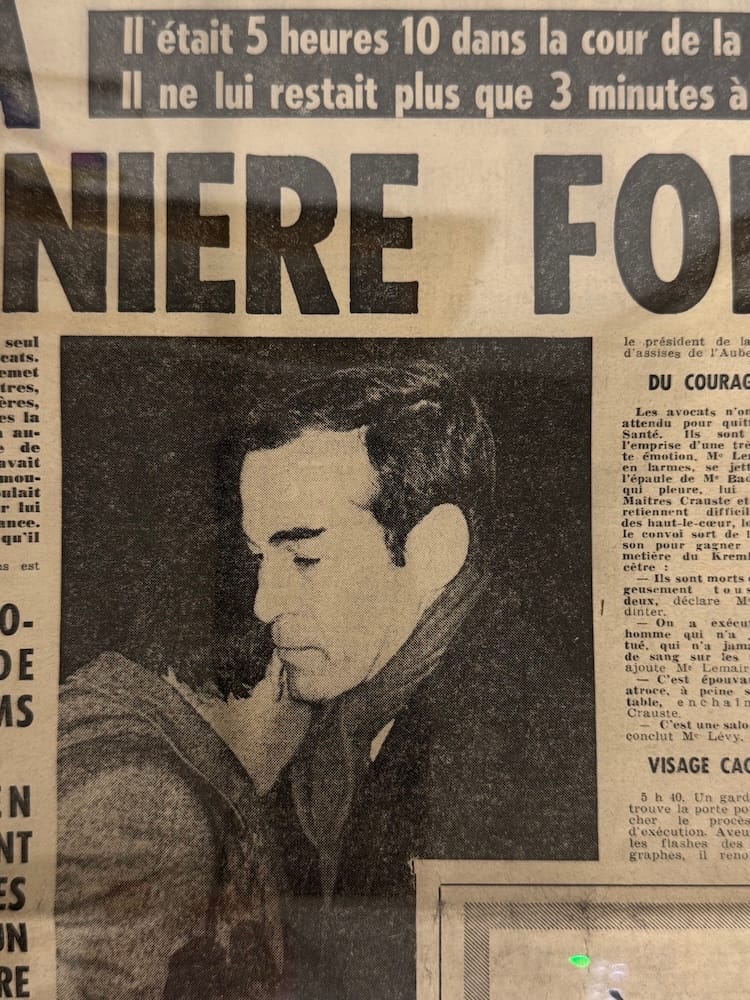

In 1972, Badinter attended the execution of his client Roger Bontems, an accomplice to a dual murder. Already shocked that a man who had not killed could be killed by the state, the renowned lawyer was devastated when he saw the guillotine in action (particularly the sound of the head hitting the ground after the blade fell) and vowed to fight for its abolition.

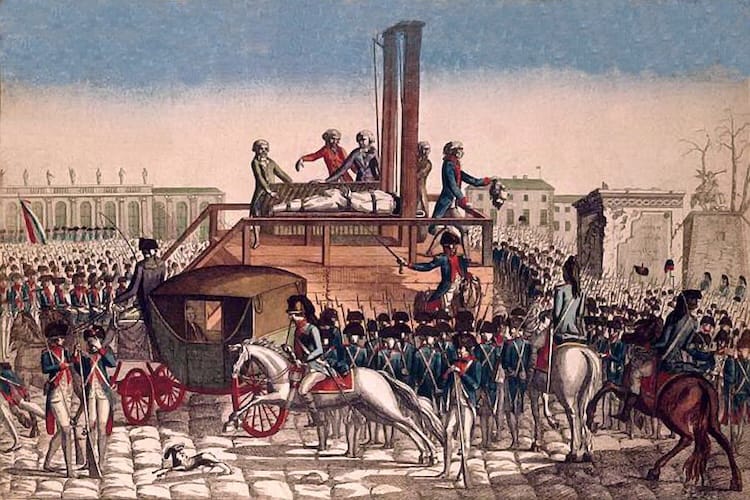

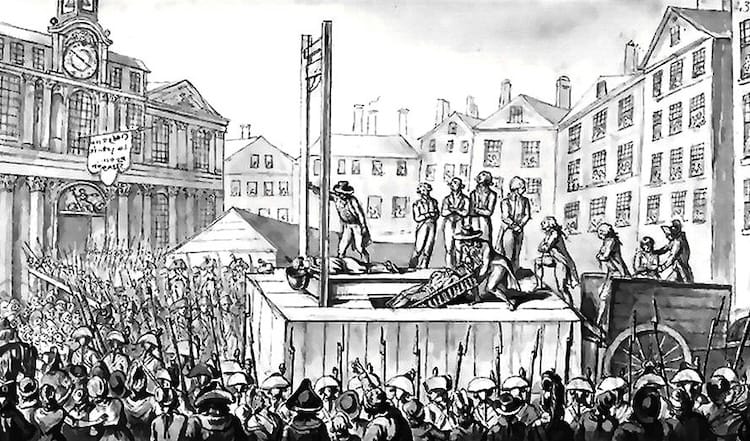

The fanfare around the Pantheon ceremony got me thinking about the ghoulish guillotine, sole method of capital punishment in France from 1792 to 1977. The machine was in fact devised post-Revolution as an improvement on previous techniques. Until then, the job of le bourreau or henchman was messy and often protracted. Nobles’ heads rolled under the sword, but not always smoothly; non-nobles were hanged, burned or – for regicide – drawn and quartered.

Although crude decapitation instruments had been used all over Europe for centuries, the guillotine in its perfected form was a Franco-German team effort: conceived by Dr Antoine Louis (and at first called un louison or une louisette), constructed by German piano maker Tobias Schmidt and promoted by Dr Joseph-Ignace Guillotin. The good doctor G argued before the newly formed legislature in 1792 (189 years before Badinter pleaded for abolition) that this modern invention would punish both Royals and Republicans equally and humanely. The victim, he said, felt “at most a cool breeze on the neck”.

Dr G enthused further: "With my machine, you can chop off the head in the blink of an eye, and you won’t suffer. The mechanism falls, the head flies, the blood spurts and the man is no more.”

La Veuve (the widow), as she was nicknamed, was so efficient that group executions became common...

Gruesome, yes, but any more so than the drawn-out deaths by injection in the United States?

I discovered that the foundation stones for the guillotine that served between 1851-1899 have been left in place at the corner of the rue de la Croix-Faubin (my markings in red; two of the stones are parked upon and barely visible) and the rue de la Roquette, site of the eponymous prison where those sentenced to death were detained before their public execution.

As for seeing a real guillotine, one was apparently on display in Marseille the day of Badinter’s service, but I found this three-quarter-sized model...

...at a museum I didn't even know existed until well into my guillotine research. Le Musée de la Préfecture de Police, housed in a police station in the 5th arrondissement and one of the stranger places I've ever visited, recounts crime and punishment in Paris since the 17th century. Though the above is a replica, the real blade that chopped off the heads of Louis XVI and Marie-Antoinette, as well as Robespierre and Danton, on the place de la Grève, now the place de la Concorde, glints before you...

Given his personal history, Robert Badinter might well have taken a vengeful approach to justice. His Jewish immigrant parents brought him up to love a France that was the first European country to give Jews rights, that ultimately exonerated Jewish Captain Alfred Dreyfus and in 1921 gave them refuge from pogroms farther East. But it was the same France that in 1943, with help from the Nazis, arrested 14-year old Robert's father Simon and sent him to be murdered in the concentration camp Sobibór. A maternal uncle who lived in France was also killed in the Holocaust.

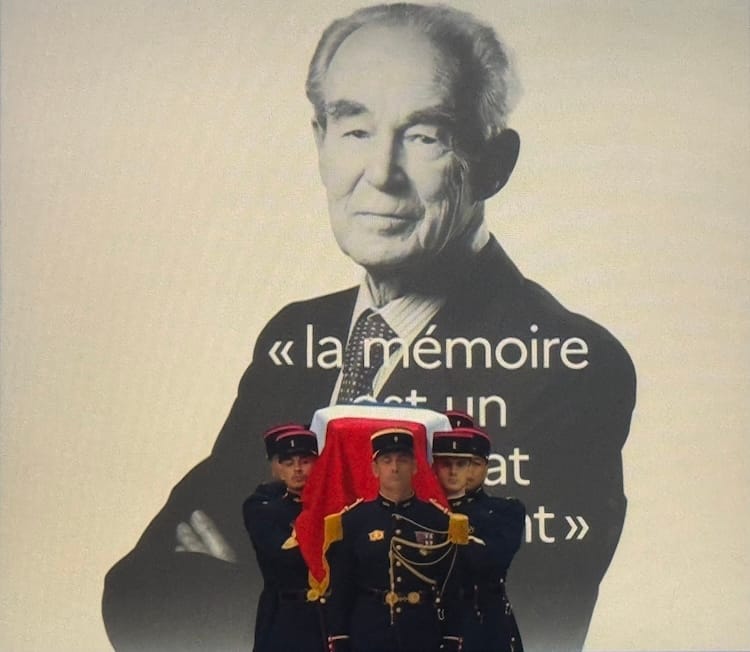

But Badinter chose the route of clemency and human dignity. He believed in learning from history, even though "la mémoire est un combat permanent""(keeping memory alive is a constant battle). Such as the conscious effort required to pave around those guillotine stones near the old prison, even 126 years later. Or, as an example of a battle lost, the wanton destruction of the 123-year-old East Wing of the White House in Washington, DC last week.

After forcing through the abolition of the death penalty against fierce opposition, he went on to fight anti-semitism and defend same sex relations and other human rights causes. He believed that jails should rehabilitate people rather than merely punish them and worked towards improved conditions and prison reform.

His positions meant he was hated by many and regularly received death threats. The morning of Badinter's entry into the Pantheon, his tomb in the Bagneux Cemetery was desecrated by graffiti that called him a defender of assassins, paedophiles and rapists.

I did not join the crowds gathered on the rue Soufflot that evening, but I did watch the ceremony on television. Everyone who is anyone in the French elite was there (though no extremist politicians from either right or left, at the request of his widow Elisabeth Badinter). In his speech, President Macron recalled the honoured man's reaction when visiting Auschwitz. Noticing three flowers growing in a devastated field, Robert Badinter said: "It was in seeing those flowers that I understood life is stronger than death." A message that in our bickering, vengeful times we would do well to remember.