Full Circle

Friday, 22 October

Late last year our son William joined the Covid-inspired urban exodus and moved from Paris to Arles, where his girlfriend Margaux was already living and where he'd spent the various lockdowns during the pandemic.

We visited for the first time last weekend. As the high-speed TGV train hurtled its way south, I watched the terrain change - flat, hilly, flat, hilly - until the cypresses began to appear on the horizon, and it was the visual equivalent of an electric jolt. It had been a long time since I was last in Provence.

Margaux moved to Arles three years ago to attend a masters course at the Ecole Nationale Supérieure de la Photographie. She graduated in June and now, like William, is a freelance photographer. The two commute often to Paris for work but return here, to a little house on a courtyard in the middle of the old city on the banks of the Rhône River.

We stayed at a hotel five minutes away, but nothing in Arles is very far. In fact, you can only lose your way for a few minutes before coming out to the main square or the Roman Arènes.

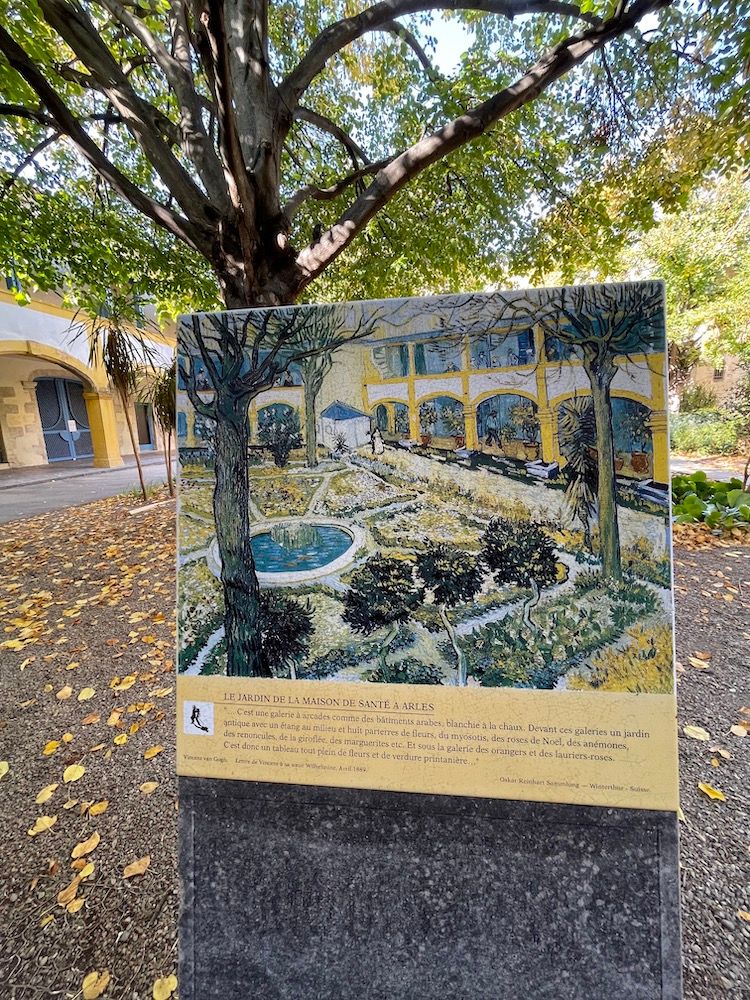

The town is pretty as a postcard and it's not surprising that Van Gogh found inspiration here, even in the psychiatric hospital where he was intermittently a patient.

The old town could have a Venice feel to it, if not for its vibrant real-life web of activity. Besides the school, there is the French photo festival, Les Rencontres d’Arles, every summer. There is a video school and a nurse’s training college. Recently the Luma Foundation, conceived and presided by the pharmaceutical heiress Maja Hoffmann, opened. In fact, according to Margaux, she owns much of the town, including our hotel. The new temple to contemporary art was built by, who else, Frank Gehry, and his tower now dominates the skyline like a bucking armadillo, after being injured by random windows.

The minute you arrive in Arles, your pulse slows and your dopamine levels soar. The languid pace allows you to appreciate the narrow streets and old stone, encourages the flâneuse in you.

On the outside I may have been strolling, but inside my neurotransmitters were in a frenzy. Arles reminded me so much of nearby Aix-en-Provence, where I lived for several months on a post-college adventure.

Even the air at this time of year, warm days and cool nights, brought back arriving in Aix early September with my friend Victoria. Towering plane trees shaded us from the sun during our first café lunch on the cours Mirabeau. We were drawn to the terrace by the bottle of olive oil on the table and were not disappointed. The tomatoes were the pulpiest and tastiest I’d ever put in my mouth. Unlike the watery, horizontally sectioned specimens of my youth, they were sliced vertically. I’ve been cutting mine top to bottom ever since.

A trip to the Saturday Arles market with William and Margaux triggered other memories of gustative epiphany, including the day Victoria and I bought our first fresh figs. Unable to wait until we got back to our one-room eyrie overlooking the statue of a wild boar on the place Richelme, we scurried behind the stand like Eve with the apple. Pulling out the squishy fruit from the paper bag, skins bursting at the seams, we thought the merchant had cheated us, taken advantage of foreign ingénues - until we bit into the sweet flesh, licked the syrupy juice from our fingers. The world was a different place when we returned to the market alleys and resumed our shopping.

The people we met, too, left their mark. There was the friend-of-a-friend cabinet maker Stephen, whose English father had decamped before he could learn the language. He invited us to supper our first evening. We ate ratatouille and drank red wine out of Pyrex glasses under the eaves next to his atelier with a group of his arty friends. They talked without interruption and laughed a lot. I understood almost nothing, felt stupid and hopelessly uncool, almost humiliated.

There was the high-minded couple, English Emma and French Nicolas. Over a lentil salad, he held forth on the superior French view of sex. After all, he said, we call an orgasm la petite mort, consider it a near-death experience.

Another English woman, Jane, a cousin of my oldest friend Helen, was an artist and the widow of a French painter of some renown. Though Jane was the age of my parents, her bohemian life mesmerised me, showed me a whole new way of being a grown-up. During the tour of her house on the hills outside Aix, she pointed out the beauty of the old roof tiles. They were irregularly sized, she said, because the roofers used to shape them on their thighs.

After the market, William and Margaux made us a delicious seafood lunch of Camargue oysters, then shrimp with locally grown olives and tomatoes, that we ate under the awning of the small terrace at the top of their house.

That afternoon we squeezed into their 20-year old Panda and drove to la Camargue, the marshy, salty Rhône River delta area just south of Arles. It's a large nature reserve where Camargue horses roam and pink flamingos flourish. Maja's father Luc Hoffmann, an environmentalist and ornithologist, put his fortune to good use here (some also has gone to one of David's foundations, PONT). On a calm day, it is almost eerily peaceful.

Over three days - where they fed us again, guided us to the most charming corners, introduced us to their favourite restaurants - William and Margaux offered us a privileged slice of their Arles life.

When we left on Sunday, I was thinking how my four months in Aix had come to form the building blocks, the foundation of what a couple years later would become my life in France. And how here I was now visiting my son, just as cool as those people I’d admired decades ago. The full-circle feel of it was very gratifying.