History Lessons

Friday, 25 September

As I was saying last week, before a fire interrupted me:

Sometimes I look at the barn we are turning into living space out here in the Perche and am surprised it’s still standing. The masons, back from their summer holiday, have continued to blast holes in the walls for more windows and doors. Meanwhile the terrassier has got to work and added his own holes while digging trenches for plumbing and electricity. It can be hard to see the creative side to our current destruction.

Meanwhile this last month we've been learning a lot about the long history of this property. Local historian Eric Y, whom we commissioned to document it, came by in August to show us the original deeds and to whet our appetite with some of what he had already learned. The day before the fire he delivered his final three-volume report.

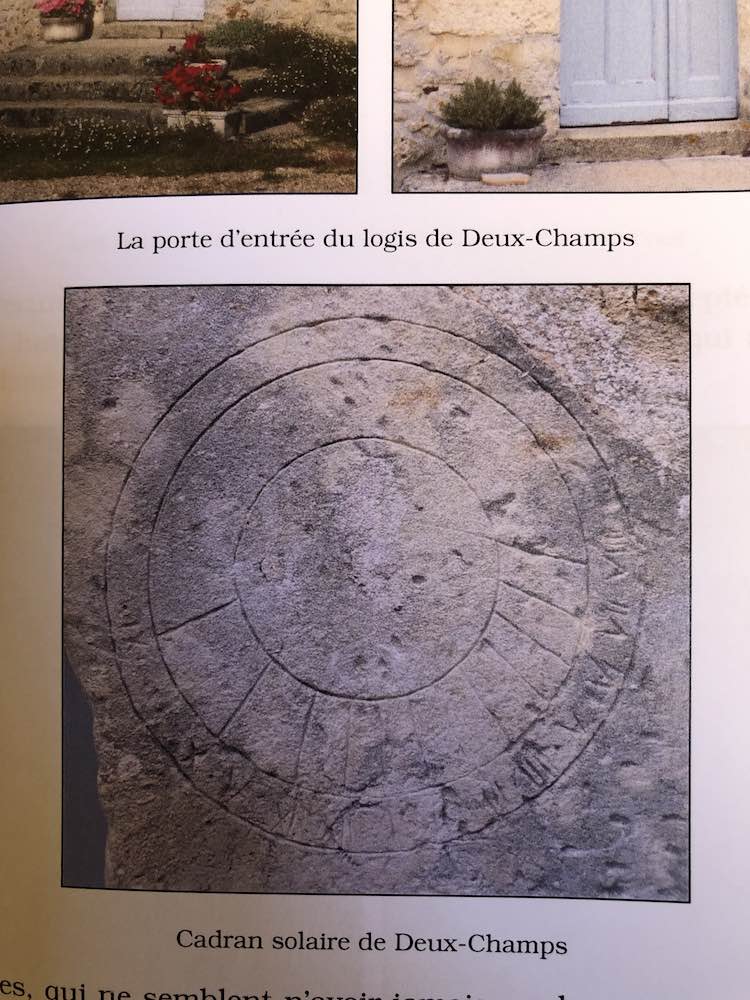

His thorough account provides a general history of the property, a detailed register of all the owners, as well as their genealogies. There are photocopies of some of the old deeds and transcribed extracts of others, as well as of leasing contracts. There are photos of notable architectural features.

In the earliest existing written records from the 15th century, Deux Champs, surrounded by fields as its name indicates, consisted of the ruins of a château on the spot where our barn-in-transition now stands, plus four farmhouses with various outbuildings, a garden, an orchard and a vineyard.

The first surviving property transaction is dated 21 December 1469. Jean Louët, lord and overlord of Deux Champs, signed an agreement to rent some of his land to Jean Culaiou, whose descendent Yves Culaiou would build the house in 1587 that we would buy almost 450 years later.

Until the French Revolution Deux Champs was governed by a suzerain direct (direct lord), who was in turn beholden to a seigneur suzerain (overlord). Interestingly, these lords could be ladies. Charlotte Angélique de Cochefilet, lady of Vauvineux, of les Chaises, of Montraversier and of Deux Champs, wife of Charles de Rohan, prince of Guéménée, 5th duke of Montbazon and peer of France, for example, inherited the title in 1661.

Things took a pedestrian turn after the Revolution, when Deux Champs became just a farm, owned and run by commoners with shorter names and no titles.

The property documents throughout the centuries choreograph a complicated dance of land parcels being bought, sold or leased, of the property changing hands entirely. The Paigné, Culaiou, Brisard and Poitevin families were pre-Revolution proprietors and the Bourgeteau, Aubert and Lesueur post. Fortunes rose and fell as people married and had children. Or didn’t. Issaye Matthieu Poitevin, a wealthy 18th century curate, passed on Deux Champs to his curate nephew Jean Matthieu, who "must have died" during the Revolution (we can imagine not of natural causes).

It does seem that offspring who were only children (except for poor Jean Matthieu) generally consolidated or expanded land ownership, at least partly because they didn’t have to share the goods with multiple siblings. In the mid-17th century Reneé Culaiou, for example, only child of Yves, inherited this house that her father built but no land. She and her husband Pierre de Brisard set about buying up lots in an attempt to reassemble the estate as it had been before being split in three by Raoul Louët's 1525 succession. Much later, in the late 19th century Jean Aubert and his only son Jean Félix, had equally acquisitive instincts. It was an affluent Jean Félix who built the barn we are now renovating.

Not all only children, however, assumed the land-owning mantle willingly. In 1931 Camille Lesueur, according to recent testimony from his daughter Colette, was forced by his parents to take over the farm even though he wanted to be a mechanic. It was only after the death of his mother in 1962 that he was able to sell most of the property and set up a garage in the nearby village.

Monsieur Lesueur sold to Monsieur B, after whom the house and land were once again separated.

The house went to the Poussiers, then Corinne and Frédéric, then us. The land was bought by Monsieur L and we bought it from him. For the moment he still farms the fields; it was his corn that almost went up in flames last week.

Though getting all this straight was not easy it was worth the effort. Property documents can highlight some interesting historical quirks. Several early owners converted to Protestantism, until the Edict of Nantes promoting religious tolerance was revoked by Louis XIV in in 1685. Contracts in the years following the Revolution used the French Republican Calendar and are dated 22 vêntose year III or 26 messidor year X.

Property arrangements can also be a window onto how people lived. Until well into the 19th century leaseholds always included more than mere monetary remuneration. In 1716, Mattheiu Poitevin, a lawyer and father of the curate Issaye, rented out the farm and retained the right to use the house whenever he wanted (it does not stipulate where the Peigné family was to sleep during these visits). The renters also had to provide him with “20 pounds of fresh butter every September, 2 capons for Christmas and one day’s use of the horse cart harness." Furthermore, they had to take proper care of a pear tree located “in the hedge, at the top of the orchard. The fruit must be picked and delivered to the landlord, at his home.”

Curate Jacques, the one who didn’t survive the Revolution, expected 1 fattened goose, 4 capons for Christmas and 4 chickens for the feast of St John the Baptist from his lessors. Had he lowered his demands he might have fared better.

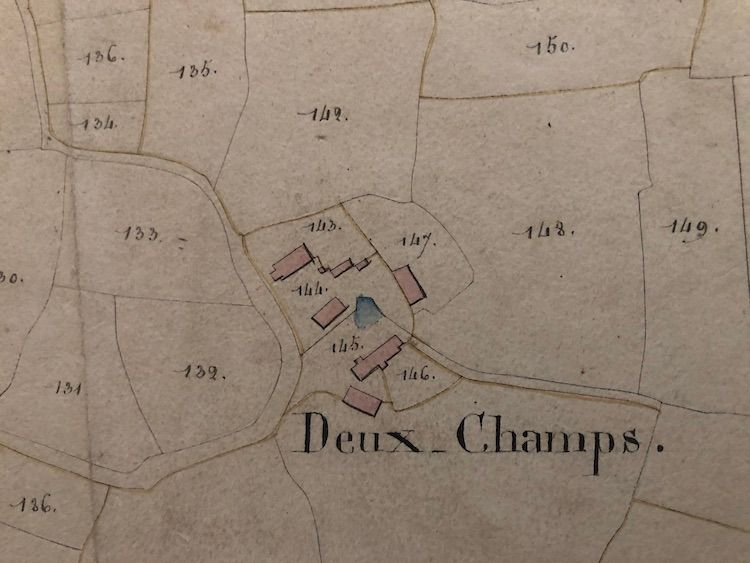

As owners have changed, so have the buildings. If you look at the 1823 land survey map at the top, only two of the structures exist today, our house and the bakery, which used to be twice as long and was home to the resident bull.

Monsieur B told us he filled in the pond in front of boulangerie that you see on the map but not in the above photo. Monsieur L told us it was he, at the request of the Monsieur B's ex-wife, who tore down the barn built in 1578. The next owners eliminated a stone spiral staircase in the main house that went from the cellar to the attic.

While these relatively recent losses cause a pang of regret, it's important to focus on what is quite amazingly still here after all these centuries. As I illustrated in the blog post following Eric's first visit, not that much has changed in the house. It's therefore easy for me to imagine Renée Culaiou or Anne Boussart, also wife of a lawyer (Matthieu Poitevin), walking out the same front door in the morning to walk their dog. I can see Marie Jeanne Aubert poking logs in the same fireplace.

When you buy an old house, you're very much a successor to all those who have come before you and a caretaker for those who will come after. Though our renovation project is taking the house firmly away from its agricultural roots, we have bought back at least half of the property's former 41 hectares (101 acres) and are developing plans to re-green it in a 21st century way. With luck by the time we are just two more names on the list of Deux Champs proprietors, we'll have done our bit and left a creative mark.