Mira-cle

Friday, 12 March

“What if she’s late?” Georgina asked when we were planning a month-long London trip to coincide with the birth of her and Amal’s baby, our grand-daughter.

An astute point from the mother-to-be. Humans can land on Mars and engineer genes, but much of the birth process remain scientifically elusive. Only 6% of babies, for example, are born on their due date (24 February in this case), an unsurprising fact when you consider that there is not even a universal standard for gestation. The British call it at 40 weeks, the French at 41 and no wonder we have Brexit.

We duly extended our trip by a week and rented a mews house in Hampstead so that once we'd finished our six-day Covid quarantine, we could form a ‘bubble’ with Georgina and Amal and help when the baby was born. By the time of our liberation, Georgina’s bubble looked ready to burst any second, an assessment confirmed by the midwife three days later. “Some time in the next week,’ she said.

We speculated on which day it would be. I pinned hopes on friends' birthdays, while Georgina, who had just stopped working and was happy for some calm before the storm, looked to the end of the week. David was shooting for the following Monday and the last in a long line of important Zoom meetings. As the days came and went, Amal refrained from predictions. One minute he wanted her to come right away, the next he thought she was fine right where she was.

His daughter-to-be apparently agreed. As one Groundhog Day flowed into another, we stopped conjecturing. We had some nice meals together. David and I went for walks together or with friends (one-on-one, per English Covid rules) in the enchanted tree world of Hampstead Heath.

I wandered around the cemetery at the church around the corner, an activity that might appear morbid, especially while awaiting a birth, but one that I find calming, a quiet reminder of the life cycle.

There's not much else to do in London during this Covid Era. With restaurants, museums and non-essential shops closed, with indoor meetings on a cold March day impossible, the wait seemed really, really long; our presence trifling.

Last Thursday—eight days late by British standards but only one by French and now almost three weeks into our visit—Georgina saw a doctor about whether or not to induce. She could wait until Monday, he said, but if the placenta started to deteriorate, the risk of still-birth would increase. Induction the next day, on the other hand, might mean resorting to forceps, ventouse suction or even a caesarean. "It's up to you," he said.

Or up to the baby: given those unpalatable options, she understandably decided that very night the time had come to move out of her warm, snug home.

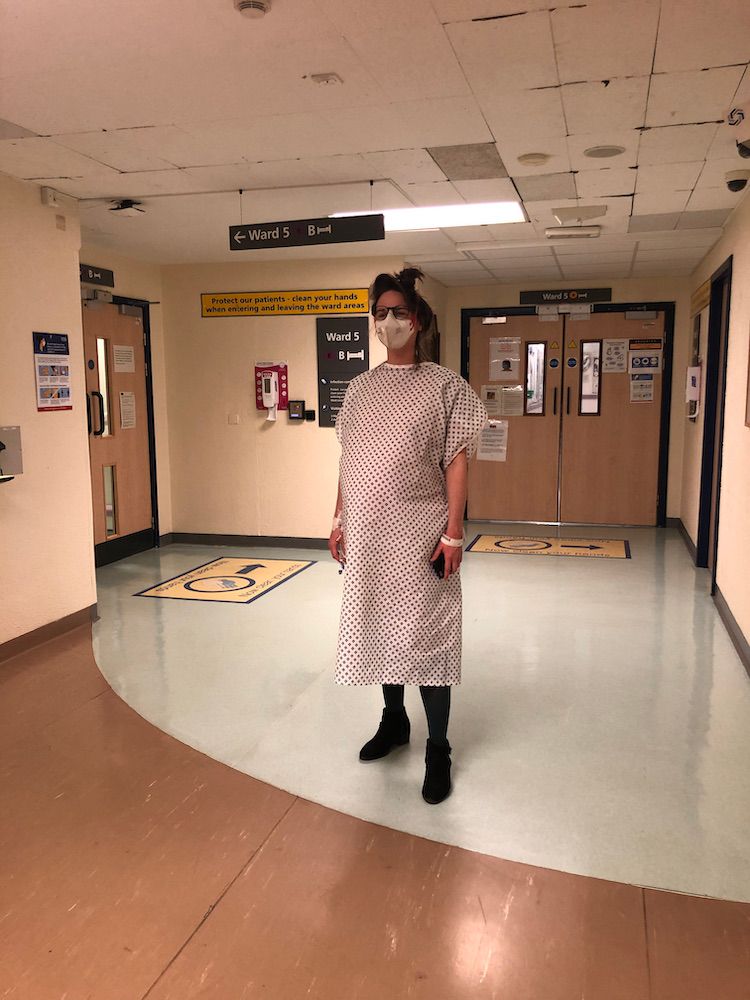

But again she was in no hurry. The hours ticked by all Friday with little change in the frequency of the contractions, even with Georgina bouncing on a birthing ball and pacing the corridors to help speed things up.

Finally, 26 hours later, at 4.12am, Saturday March 6th, Mira Fleming Kothari, all 3.76kg (8.3lb) of her, was born.

Usually I think of myself as a fairly objective person, at least someone able to discriminate between my heart and my head. But when I met little Mira, still cone-headed and flat-faced from her descent down the birth canal, I could only see perfect beauty, a little bundle of flawless humanity whose downy head, tough little limbs and silky skin caused an unruly burst of joy and love. Not quite as explosive as when my own children were born but closer than I’d expected.

It must be wired into us, that tidal pull, and thankfully so. The first weeks are gruelling and rewards are limited; a newborn is not much more than a digestive tube that sleeps or cries in between the milk going in and coming out.

Georgina’s body is ravaged—she can’t walk much farther than from one feeding station to another—and both parents are exhausted, grabbing a couple of hours sleep whenever Mira allows. “Day and night,” Georgina said, “it’s all the same to me right now.”

David and I have finally been able to help a bit. Cleaning and tidying, doing the laundry and the shopping. Even just holding the baby for a while. David has not lost his touch.

Around 1am last night, I worried that I had lost mine. Having stayed over to let the beleaguered parents get some sleep, I could not settle the baby who had just left Georgina's breast. Amal came out and shoved a bottle of Georgina's expressed milk into Mira's searching mouth like an old pro. When she'd polished off that and was still fussing, I sent him back to bed. But on she fussed until finally, worn out, she fell asleep in a ball on my stomach.

In the early morning light, with Mira still curled in my arms, grand-parent-hood seems a very privileged vantage point. Though exhausted now myself, Georgina will wake up when Mira does and take over. After I've tidied up and done some shopping for them, I'll go back and rest, undisturbed. Tomorrow, refreshed, I will notice the little changes that even 24 hours bring in the life of a newborn.

Grand-parent-hood gives you perspective, a distance in time and space from the immediacy of parenthood. It means I have greater sympathy for little Mira and what a struggle it must be for her to adapt to this harsh world. I can admire my daughter, remember how motherhood, despite the pain and fatigue, makes you feel invincible.

And I can tell Amal, worried about his role, that especially in the age of milk pumps, he still has a lot to do. That it's only the beginning and Mira will need him in ways he cannot even imagine now. That one day they may look back on these demanding days as some of the most magical in their life.