Safe Havens

Friday, 14 October

Every morning I do a stupid thing. After some work and before walking Tasha, I peek at the news in the The Guardian's newsletter that arrives in my email box. Yesterday the cover photo showed four soulful sea lion pups and the headline said: "The Age of Extinction: almost 70% of animal populations wiped out since 1970," with us humans as the cause. Meanwhile, long Covid is ruining the lives of millions, further straining overburdened healthcare systems and even affecting workforces. With winter on the way, the virus is again on the rise, along with the price of fuel (in France a strike is making the vehicle variety virtually unavailable) and the general cost of living. Most days there's a really scary article predicting how serious Vladimir Putin is about using nuclear weapons and what will happen if he does indeed push the button.

Already feeling shaky, I cross our courtyard with Tasha. It looks like this:

I open the door onto the street and we wriggle through this:

On the rue de Solférino, we squeeze by this:

And it's only 7.30am.

Thankfully, Paris is more than her slatternly outward appearance these days implies. She has a rich interior life, a vast store of inner resources, including her 200+ museums, which offer both edification and refuge from outside chaos and depressing news. Now that the tourists have returned, the bigger, better known establishments such as the Louvre, the Musée d’Orsay or even the Orangerie, are packed and not much of a relief. But there are a trove of smaller museums all around the city. Generally, they are housed in beautiful places and are havens of tranquillity.

One of these gems is around the corner from us, on the rue de Lille. In 1947 the Dutch art historian and collector Frits Lugt bought an hôtel particulier (grand townhouse) and created the Fondation Custodia (for a long time known as the Institut Néerlandais) for his collection of 19th century European art, mostly drawings (7000) and prints (15,000). The Fondation displays a smattering from its permanent collection but also organises exhibitions. I visit often.

The stress nodes stop vibrating the minute you walk under the porte-cochère.

The foyer still looks like a well-kept residence.

Upstairs are the works from the permanent collection. As you can see, crowds are usually not a problem.

The basement is reserved for temporary exhibitions, and yesterday afternoon, alerted by my friend Louise D, I went to see a new show that was the perfect antidote to the morning's assault on my senses and sensibility:

Léon Bonvin was the younger half-brother of the better known François Bonvin. After a hardscrabble childhood, he reluctantly ran the humble inn inherited from his father in Vaugirard, then a small village and now the XV arrondissement of Paris, but he dreamed of living from his art. The early works were pencil drawings that recorded the world around him, including the café, outside...

...and in...

Gradually he brought in watercolours and shifted to nature as his main subject matter, first in Dutch or Chardin inspired still-lifes.

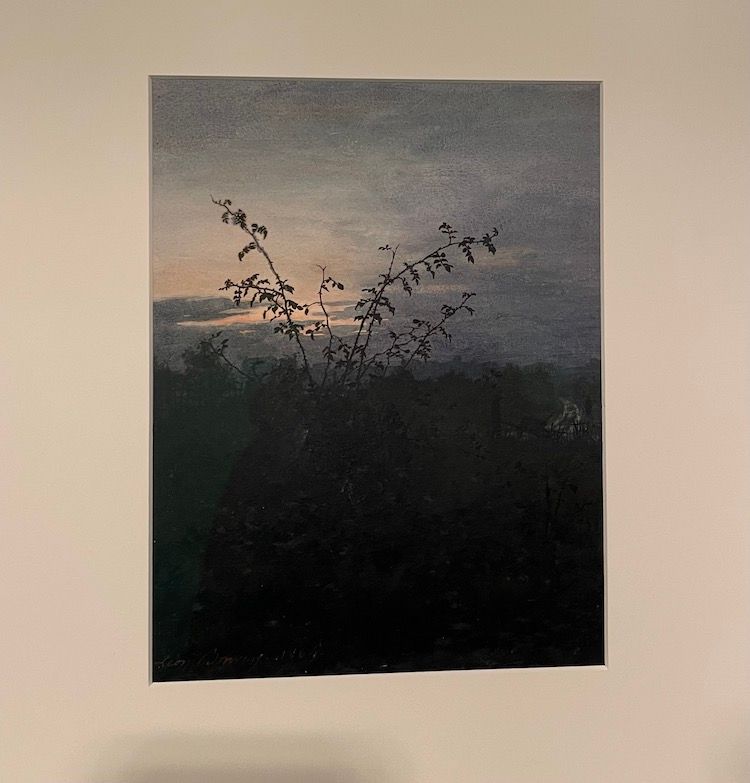

And later as scenes from his morning rambles around the Vaugirard countryside.

Walking through a retrospective, you are plunged into the artist's life, are taken step by step along the creative trajectory. You see how one theme or technique spins into another, meanwhile following the threads that are constant throughout. It's always an intense experience, but at a blockbuster show in a big museum, the force of the encounter is tempered by bobbing and ducking to see the art and, in my case, by fighting agoraphobia. Often you're already acquainted with a substantial part of the famous artist's oeuvre.

With Léon Bonvin, in the windowless, all but empty basement of the Fondation Custodia, it was pure discovery, an uninterrupted moment of deep connection. The delicate intimacy of his work was both exhilarating and familiar. It moved me deeply.

I don't have to look far to know why. No further than my own photographs, which echo his perspective...

...subject matter...

...and choice of silhouette during country morning walks...

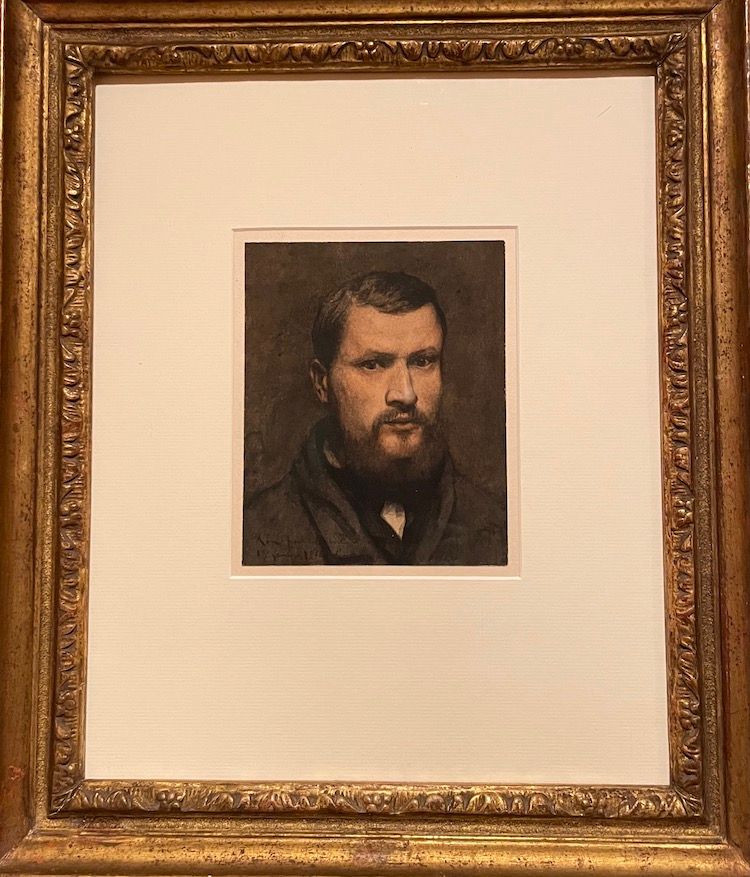

Often at exhibitions I don't pay much attention to the biographical information until later; I like to experience the work in isolation from the life. So it was a shock when I got to the last room of his paintings, and my eye caught these words: “In January 1866, Léon Bonvin committed suicide in the Forêt de Meudon.” The text was right next to the show's only self-portrait, painted 10 days before his death and dedicated to his wife.

It was like hearing tragic news about a person I’d recently struck up a friendship with, but given the melancholy strain running through his work, the shock was not entirely a surprise.

Despite his sad end, I emerged from the museum feeling spiritually richer and - even if it won't last - sublimely removed from the troubles of the temporal world.

Needless to say, I highly recommend the Fondation Custodia, both its permanent collection and the Léon Bonvin exhibition, on until 8 January 2023. Just don’t tell too many of your friends.

___________________