Steep Steps

Iranian woman and tourist overlooking Persepolis

Friday, 14 October

I have just returned from a trip to Iran, and one of the first things I noticed, besides many women swathed in black, were the steepest steps I've ever seen. They were everywhere, from mansions and palaces to mosques and ruins.

Why, I wondered, given how sophisticated the architecture is, weren't the stairs more gently graded?

Aghazadeh, Abarkooh

After a few days it started to make sense. Iran is a very complicated, contradictory place—certainly much more nuanced than a lot of media reporting would lead you to believe. It's the size of the UK, France, Spain, Italy and Switzerland put together. Its first great civilisation dates back to the 6th century BC and comprised an empire that stretched from Europe to northern Africa to the borders of China. A deep understanding of it would require a long, hard climb.

Even the experts can be stumped

But at the end of two weeks and almost 2000 kilometres by land under the tutelage of learned and articulate guides, our group did, maybe, crack the surface.

The trip began with a couple of days in Tehran, the population of which has ballooned over the last 25 years from 6.5 million to 14.5 million. The multi-lane highways that cut through the city, the dense, haphazard construction...

and bizarre street art displayed on meticulously tended patches of greenery...

give it a futuristic feel. Traffic is abominable, as is pollution, but there’s a beautiful palace...

Golestan Palace

and some wonderful museums...

Our erudite and energetic guide Mr S with Darius the Great, National Museum

Reza Abbasi Museum

that provided a good introduction to what we were to see subsequently.

On one level the history of Iran is a repetitive saga of boom and bust. Glorious periods of scientific and artistic innovation, of economic prosperity and tolerance fluctuated with centuries of invasions, occupations and violence. By the 19th century Iran had become of strategic importance in the Great Game between Britain and Russia. On our trip, in fact, were the grand-daughter and great grandson of one of the players, Sir Percy Sykes, British Consul in Kerman and general Iran expert. Hearing about his life was a reminder that once upon a time, Europe was heavily invested in Iran and its future.

'Mrs Percy', as Mr S and soon all of us called her, with son Adam, in front of the old British Consulate, Kerman

Perhaps the most spectacular manifestation of this boom and bust cycle is Persepolis.

Gate of All Lands

It was built as a ceremonial palace by Darius the Great in 519 BC to the glory of the huge, prosperous and relatively tolerant Achaemenid Dynasty. It is a masterpiece of architecture, stonework and sculpture.

And it was overtaken, pillaged and burned by Alexander the Great in 330 BC. As our guide there Mr B said: 'It's the same story over and over again. Dynasties rise and fall and no one ever learns anything.' (As frequent readers of this blog will know, a theme dear to my heart!)

But what people did learn was how to tame the harsh climate of southern and southwestern Iran. On a high, dry plateau, some of which is natural desert, some of which has suffered from deforestation...

This is not a desert

...man is face to face with the elements and it's not surprising that a tenet of the pre-Islamic Persian religion of Zoroastrianism (still alive and kicking in places such as Yazd and via the Parsees in India) is the balancing of earth, air, fire and water.

Mountains loom romantically in the distance on both sides of the plateau

Very early on they came up with ingenious survival tactics. Water, obviously scarce on this dry plateau, has been brought down from the mountains since the 1st century BC via underground channels, or qanats, to supply houses, villages and cities; to irrigate fields and orchards, as well as the many spectacular gardens.

Because of extreme desert temperatures, mud brick, an excellent insulator, was used to build fortresses...

Rayen

...hunting lodges...

Following our fearless leader, Mr S

...and humble huts...

Jupar

Wind towers or bagdirs were developed as an ur-air conditioning system: hot air is funnelled down the chambers into a pool of water which sends cooler air throughout the building.

Yazd

Mosques are of course everywhere.

We visited many, many of them, from the earliest 10-12th century monochrome buildings of brick, stone and wood (my personal favourites)...

Friday mosque, Natanz

...to the increasingly elaborate and sophisticated tiled post-12 century style...

Friday mosque, Isfahan (1612-38)

Our guides taught us much about Islamic architecture--the stalactite vaults and the squinches, arches (invented during the Sasanian Dynasty, they said) that allow a square or polygonal building to support a rounded dome; the intricate tile work and the layered method of painting stucco--but they also told us many stories. About the various shahs and their intrigues, about the difference between Shia and Sunni Muslims (still seems like a personal rather than a doctrinal dispute to me) and how the Iranians are not Arab and didn't have much to learn from those Bedouin invaders anyway. They also told us many Persian fables, morality tales of human folly and wisdom. And recited much poetry, particularly Hafez, the 14th century poet whose tomb we visited in Shiraz, by heart.

Mr S, extemporizing

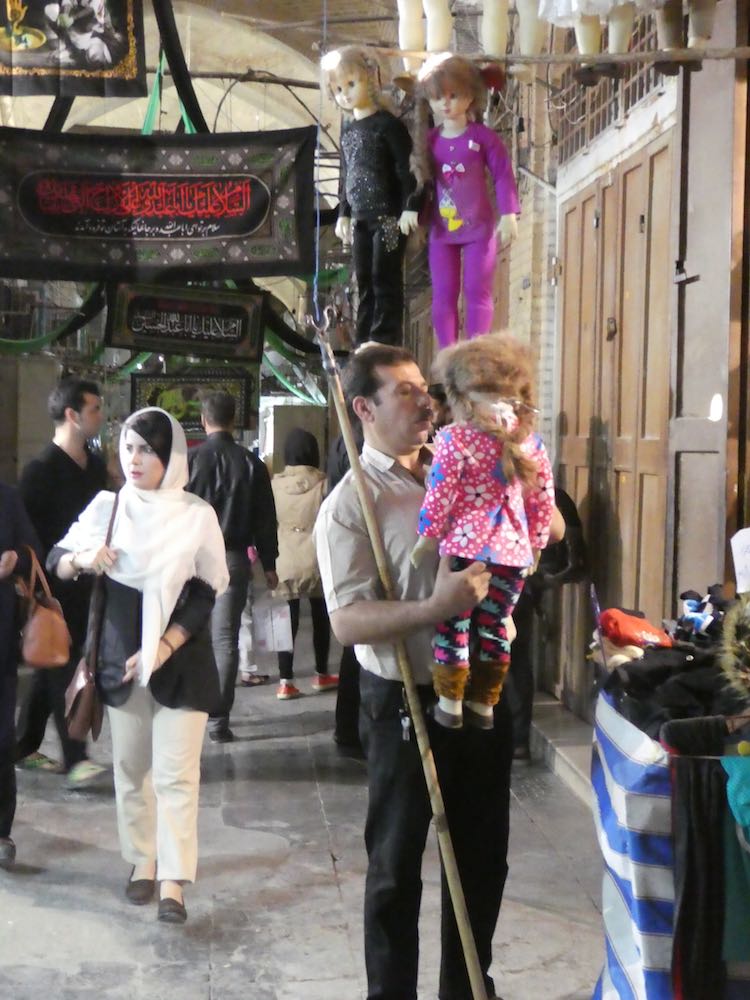

The stories and the poems were a good backdrop to what we were seeing in contemporary Iran. Mohammed after all was a merchant and the streets are lined with shops, the bazaars wind on for kilometres.

Dancing with the west

Zara chador

Higher aspirations?

The real people we met along the way were as charming as the ones in the stories--friendly, smiling...

Schoolboys, Yazd

...curious....

Shàn and Iranian man, Isfahan

We were continuously asked where we came from and if we liked their country and would we like to come in for a bite to eat...

Hospitality, Jupar

...or could they have a photo op with us...

Victoria and Iranian girl, Jupar

David and Iranian man, Mahan

...or could I take a photo of them (before they took one with me)...

Family portrait, Mahan

They were also scrupulously honest. In fact, given that a terrorist attack was highly unlikely, I felt safer there than on the streets of Paris.

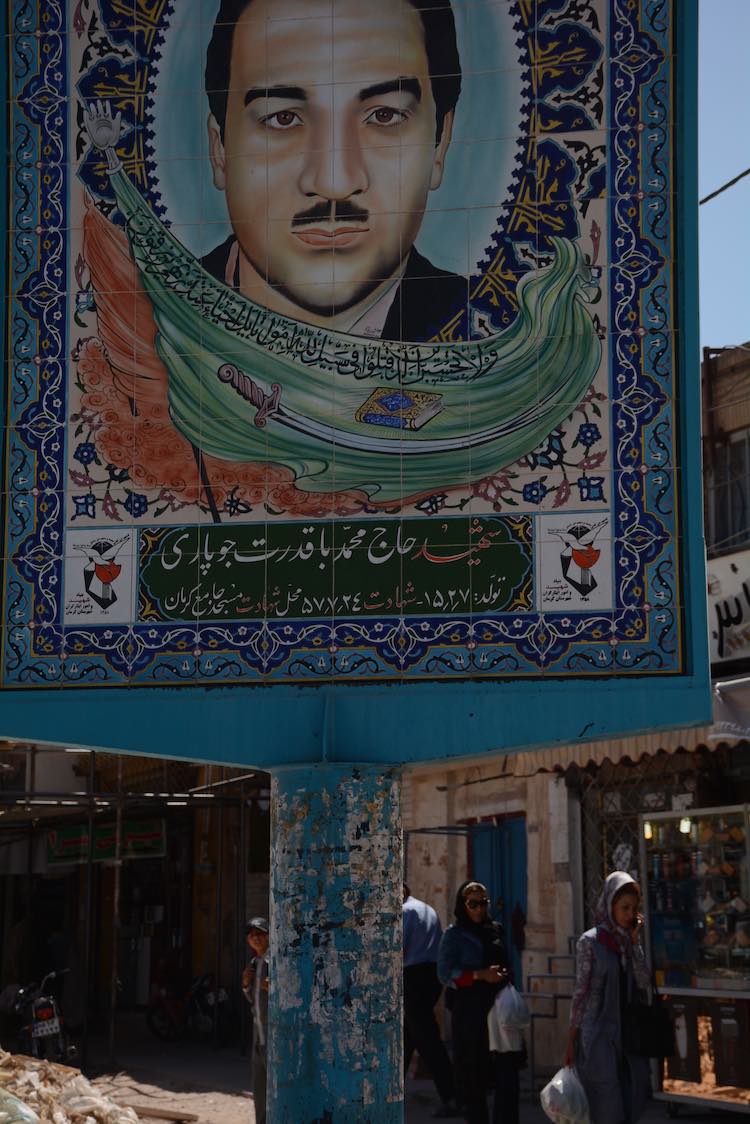

Which doesn't mean there aren't some serious downsides. The violence that has plagued Iran's history can be felt just under the surface. The various wars and conflicts in the region in which Iran is currently involved, as well as the Iran-Iraq War of the 1980s, are constantly evoked by the huge pictures of martyrs that line all streets...

Kerman

...and even get slapped on top of street art...

Yazd

These martyrs started to make more sense when, during our stay, the country began preparing for Muharram, a holy month in the Islamic calendar. For Shias it is a time to mourn the murder of Hussein, grandson of Muhammad, and 72 others at the Battle of Karbala. Black (death) and red (blood) flags and banners appear everywhere. People parade and gather in huge crowds at mosques and get whipped up to a frenzy of emotion over these deaths that occurred almost 1400 years ago.

Bazaar, Esfahan

Iran's human rights record is also less than stellar and its women, though they account for around 60% of university students, are confined to the veil (having worn one for two weeks, I can confirm it is irritating on every level) and second place in society, even if the push and pull between tradition and western influence is evident on every street corner.

Mother and daughter, Shiraz

Cowboy-hatted construction worker, Yazd

But what struck me most were the environmental challenges. Tehran's problems of overpopulation, haphazard development and pollution are mirrored in all the big cities.

Old man on bridge, Shiraz

It turns out Iranians' thirst for energy is as immoderate as ours and water, once so carefully managed, is being diverted for hydro-electricity, thus reducing lakes to large puddles (tough luck for the pink flamingoes now forced to huddle in the middle)...

Lake Bakhtegan, once 160 km long

...and leaving river beds dry (tough luck for the wetlands further down-river, where thousands of plant and animal species are now dying of thirst).

Zayandeh River, Isfahan

The desiccation was particularly eerie and unsettling because it was like looking into the world's future, to a time when no one has enough water.

It left me wondering: what will the glory of past civilisations or the intensity of current political and cultural conflicts matter, if we let the planet goes bust?