Irony and Evil

Friday, 28 August

I am looking at my old map of East Berlin, purchased in 1987 during my only visit to this part of the city before the Wall came down two years later. Just north of the Lenin-Allee and just east of Ho-Chi-Menh-Straße is a blank spot, an area where little streets appear to dead-end into nowhere.

It’s where the GDR’s political prison stood, still stands, though it's clearly marked on our current Berlin map, just north of the Landesberger-Allee, just east of the Weissensee-Straße: “Gedenkstätte, B-Hohenschönhausen.”

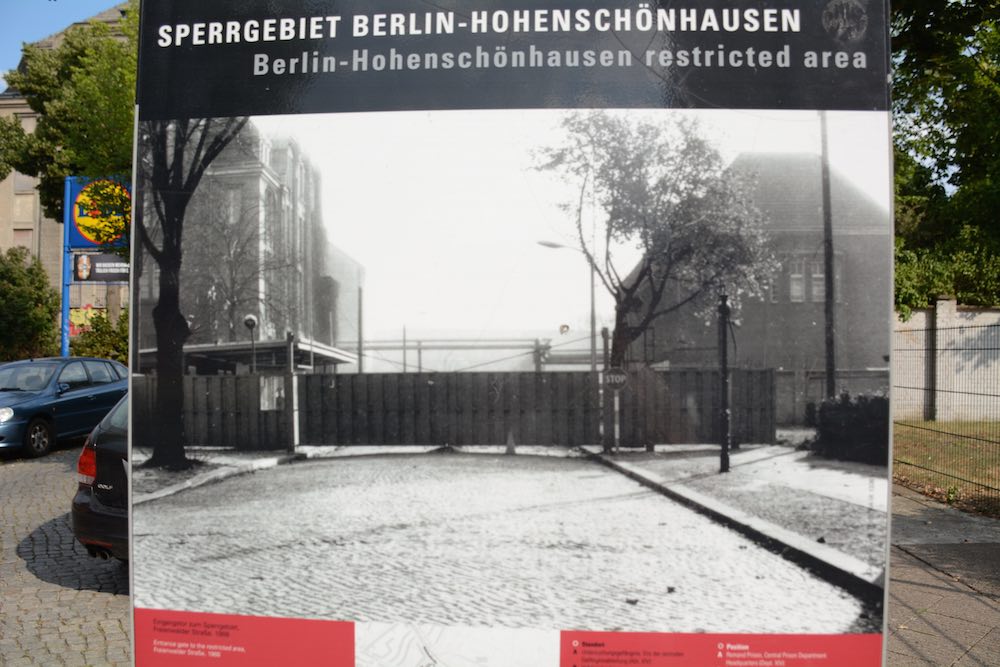

The former prison complex is a perfect storm of irony and evil. The entrance to Hohenschönhausen (high pretty houses; granted, the name is taken from the eponymous area of Berlin) was on the Freienwalder-Straße (Free Forest Street). It was originally a Fleischmaschinenfabrik (meat machine factory). I don’t know what happened to its owner Richard Heike (though the internet tells me a book was written about him) but by the time of the Second World War, the Nazis were using the area as a canteen and for food storage.

Enter the Soviets, who turned it into a prison, purportedly for former Nazis, but really for anyone they didn’t like. Prisoners were tortured and kept in overcrowded, windowless, dank cells in what they called the U-Boot, or submarine.

Conditions were not much better than in the Nazi concentration camps and several thousand are estimated to have died, their bodies dumped in bomb craters-cum-rubbish heaps.

In 1951, the East German Ministry for State Security (MfS), or Stasi, was created, and they appropriated the area, originally as a remand prison for political prisoners, then once the Wall was built, for potential defectors as well. Over the years, Hohenschönhausen expanded physically and bureaucratically, eventually housing many MfS departments, but it remains known for its core business of interrogating and tormenting prisoners.

Brute force gave way to more subtle, sophisticated tactics: extreme isolation, standing in cold water, sleep deprivation (lights on all night, or on/off every few minutes) and threats to family and friends. Indeed, the Stasi honed its creative skills to such a point, it would seem their aim was less extracting information from alleged enemies of the state than seeing how far the human psyche could be pushed, how small and miserable a human being could be made to feel. They processed people like meat.

Today the entrance has been pushed back to the Gensler-Straße. Vestiges of the factory remain on the Freienwalder-Straße. This spooky structure was used by the Soviets as their first interrogation centre and by the Stasi for secret archives on people with Nazi pasts.

Many of the MfS buildings are now used as housing. One has been turned into the Eastpax hostel, which on its website proclaims: “established 2014 in a vintage office building from the 1960ies.” Technically, I guess, that’s correct. It housed the Stasi’s arms and chemical services, also a lab for fingerprinting and hand-writing analysis. A young Dutch tourist claims on Trip Advisor, with no apparent sense of irony, since she seemed to have no idea of the building's original purpose: "The room was clean BUT we felt like prisoners."

hostel on the left, prison entrance on the right

The prison complex itself is now a Gedenkstätte, or memorial. Since the area was completely restricted and shown on all maps as a blank spot, most East Berliners knew little about the prison and therefore did not storm it, as they did the Stasi Headquarters in 1990. This meant that the authorities had time to destroy most of the paper trail, but it also meant that the site itself remains almost wholly intact.

Right down to the acrid, trapped smell. Similar but stronger than the odour at the former Stasi Headquarters. It's the smell of a place that has locked out all goodness.

With so many files destroyed, former prisoners have provided much of what is now known about the place and until recently they were the only tour guides of the prison.

The Sunday David and I visited, our guide had been arrested twice but imprisoned elsewhere, in Thüringen. He was a feisty, impassioned man, who at every stop emphasized how meticulous the Stasi was in its efforts to de-stabilize and isolate prisoners. “They thought of everything!” he said, in this case, by creating a cosy, familiar environment that was also menacing, solitary and confined.

Or "the Tiger Cage," where prisoners were taken to exercise. While patrolled by guards overhead, they had to keep moving and could not touch the walls.

He made three points over and over. One was that West Germany was so bent on reconciliation, it let almost all the Stasi off scot-free. Many, he claimed, are now in positions of power in the reunited Germany. His second point was that Nazis, Soviets, Stasi—it was all the same thing, just one long line of evil. Finally, and this is a point dear to my worldview, it wasn't very long ago. "People think it's over, we've changed. They're wrong. It could happen again tomorrow."

Freienwalder-Straße, Berlin, August, 2015

For a fuller picture, complete with biographies of some of the prisoners, look under "historical location" in this English version of the Hohenschönhausen site.