Ode to a Friend

Friday, 20 November

Almost déjà vu: the stunned hours in front of the television, the shattering feeling that nothing will be the same from now on, the worry that the centre is crumbling right before our eyes. There was even the odd coincidence of returning to Berlin the Sunday following the shootings.

This time, however, the discomfort in leaving Paris was stronger. The amplitude of the attacks was greater, the story closer to home. Even by Saturday it had come into clearer, sharper focus: William had been on the boulevard Voltaire not an hour earlier but 10 minutes; Christopher’s friend had been shot more than once, in both legs, and was undergoing surgery. Her boyfriend was taking grim solace in the fact she’d been slotted in late morning, rather than first thing.

Getting on that train Sunday morning, I had the feeling of abandoning a dear friend in her hour of need.

Because Paris has been just that: a dear friend, for now well over half my life. Still not a day goes by without my being struck by her beauty. Still I marvel at a city that manages to feel both small and big, both comforting and challenging. Taken one by one, the quartiers are intimate, familial, but jostled together they create the buzzier, electric edge of a metropolis.

It was—and I hope still is—a great place to raise children. The school was right down the street, as were the judo and chess and dance classes. There was never much need to leave the neighbourhood, except when the small children got bigger, and the city was their oyster. By 11, they were taking the Métro unaccompanied. From 15, they were allowed out on a Friday or Saturday, with later and later curfews. At 16, they could drink legally, but parents worried less because they couldn’t drive until 18 and no one had a car anyway.

Even the French education system deserves a pat on the back, a word of thanks. I admit it’s not the fuzziest, cuddliest of institutions, that it’s too rigid and stuck in its ways. But I was gobsmacked by the young witnesses and near victims, products of that system, on the French news last weekend. Despite their state of shock, sentences were perfectly composed, thoughts eloquently expressed. There was none of the sausage talk heard too often in English, where run-on sentences are so chopped up with likes and you-knows, it’s almost impossible to grasp the meaning in between.

place de la République, after one, before another...

A lot of people have called these attacks, versus those in January, random, but they seem to me just as targeted. As the wanted poster of the suspected missing gunman Abdeslam Salah has repeatedly reminded me, he was born exactly one year after Christopher, the 15 September 1989.

My Paris story has been about as close to a fairy tale as real life gets. But there’s another French narrative, one that plays out in the banlieues, the towns ringing many cities that are heavily populated by immigrants and their children. Though integration has not failed completely—the ethnic mix among the victims in the attacks is proof of that—it has failed enough to frustrate and anger a growing number of people my children's age into a terrifying extremism, one with ideals completely antithetical to those they should be learning in the French schools and in their communities. One that leads them to believe that their oyster, unavailable on this earth, can be attained by killing others wantonly, then blowing themselves up.

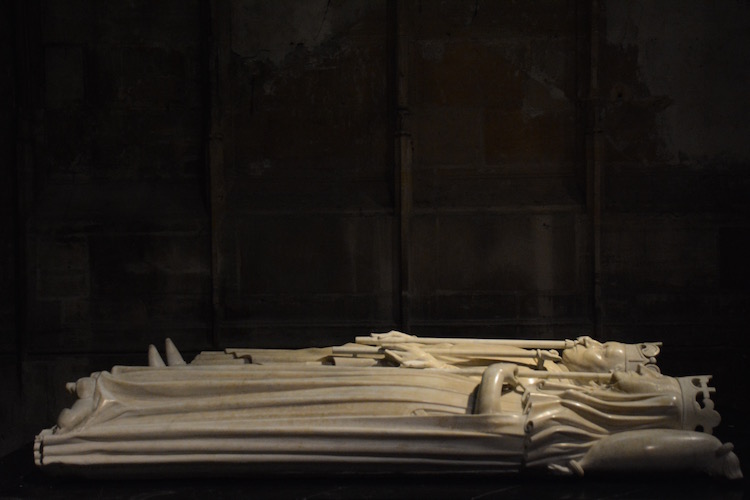

Basilque Saint-Denis, 11 November 2015

In another odd coincidence, I went to the Basilique Saint Denis last week. It was partly for my current novel project, partly because I was interested to see how the first gothic cathedral, burial place of the French kings, was holding up in the reputedly rough banlieue of Saint Denis. My last visit was in 1981.

On 11 November, the cathedral was full of tourists but the stone square in front of it was almost empty, perhaps because the town hall along the side was closed for the holiday. In any case, just beyond was a mass of people, which made the esplanade seem a shield or a buffer zone between two worlds. As I walked away, here behind me was a bastion of Christianity and French tradition, the resting place for its dead royalty. Here in front of me was a typical provincial shopping street, except that it was a Tower of Babel where I heard almost no French. Practically everyone milling about or strolling along was from elsewhere, or at least their parents were.

Two days later the attacks occurred. One week later, I turned on the television in Berlin and there was that dumpy little street, now chock-a-block full of police and security forces who had just shot 5000 rounds at a building around the corner.

Looking down the real-life street, I had not imagined terrorists nestled in there, much less the presumed mastermind Abdelhamid Abaaoud and his foot soldiers, perhaps at that moment loading their Kalashnikovs, mixing the cocktail of explosives that would allow them to self-destruct after killing as many people as possible.

But I have to say, having been there, having felt the atmosphere, I can’t say I am surprised.

In the tale of the Tower of Babel, that scary, vengeful Old Testament God says: “Come, let Us go down and there confuse their language, that they may not understand one another’s speech.” He does it to make the city, the community, fail.

I hope ours won’t, that Paris will stay Paris, but I also have to say that hope is getting harder and harder to muster.