Things, Glorious Things

Friday, 16 December

I love things. Big things, little things, things that belong to me and things that do not. Sometimes I am uneasy about this proclivity. It can seem materialistic, trifling, overly personal, boringly bourgeois.

But if the current exhibition scene in Paris is any indication, I’m right in the swing of those Things.

At the Palais Galliera, there’s “Frida Kahlo, au-dela des apparences” (beyond appearances), where many of the Mexican artist’s iconic dresses and personal effects are on display. They open a fascinating window onto her creative process and her art.

Tomorrow is the last day for the small exhibition of a little known 17th century Italian painter Evaristo Baschinis at the Galerie Canasso. His delicate, hyper-realistic still lifes of musical instruments, complete with dust and fingerprints, are technically and spiritually captivating.

Then there’s the exhibition at the Louvre, “Les Choses - une histoire de la nature morte”, a history of the still life in general. It's one of the mega-shows I recently wrote about trying to avoid: a highly praised must-see; nothing like it since its avatar in 1952…I could just imagine the hordes.

But: a whole show devoted to things? What I photograph compulsively, what I write about daily (leaning, as I do, on the minutiae of daily life to build atmosphere, plot and character). How could I miss it?

I planned the trip with care, reserving on a weekday at lunchtime and entering through the Porte des Lions side entrance. Many potential visitors were indeed eating lunch; I waited not a nano-second at either the museum or exhibition entrance and thus joined a manageable crowd, feeling calm and receptive.

The show traces les Choses that have inspired art from pre-history to today, in painting, sculpture, photography and video. The 15 sections are chronological and thematic, globally delineating how our relationship to things has become more secular over time, but there’s a lot of mixing and matching in the elegantly earth-toned gallery.

Different eras, subject matter and media sit seamlessly and evocatively side by side. So in the 19th century “The Simple Life” section, for example, you have Van Gogh’s Bedroom in Arles, 1889 (Vincent did not like things, thus the full-frontal take on his uncluttered quarters) next to another Dutch artist, 17th century Samuel Van Hoogstraten, whose tableau The Slippers is littered with objects (the abandoned slippers of the title, keys, a mop, a candle) that invite the observer to imagine the human who has just slipped away.

Or in the 20th century “In their Solitude” section, the still life artist par excellence Giorgio Morandi’s painting (1944) is bracketed by Sophie Ristelhueber's photo of shoes in the sands of Kuwait, 1992, and a clip from a documentary by the film maker Jean-Daniel Pollet (1997, God Knows What).

You also see how one style or theme segued into another. How, for example, Cézanne's breaking the line on that kitchen table led to the Cubists' fracturing of space altogether or Matisse's flattening and stylising of it.

As the show illustrates at several points, it can turn ugly when Things get out of hand. We're not the first generation to experience excess and cupidity - just look at Marinus Van Reymerswale, The Tax Collector (circa 1540) from the 16th century section "Accumulation, Exchange, Market, Pillage".

It can get sad. A later section is called "Vanity", as in a sense of futility at our mortality, with lots of rotting fruit and skulls.

In "Modern Times", artists began taking the mickey out of Things. There's a champagne bottle-holder that Marcel Duchamp in his Dada phase bought off the shelf to ridicule the idea of Art as unique creation.

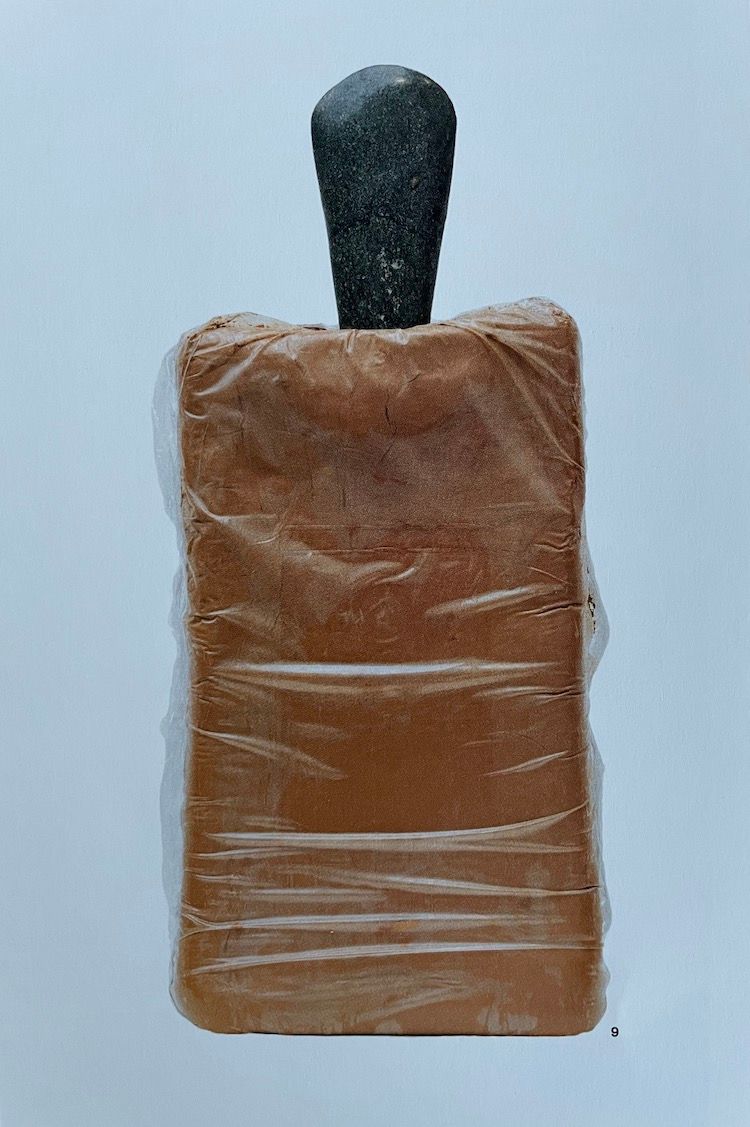

In almost every work I recognised one of my own photos, whether it was the Neolithic hatchet wrapped in clay and plastic in the "What's Left" section...

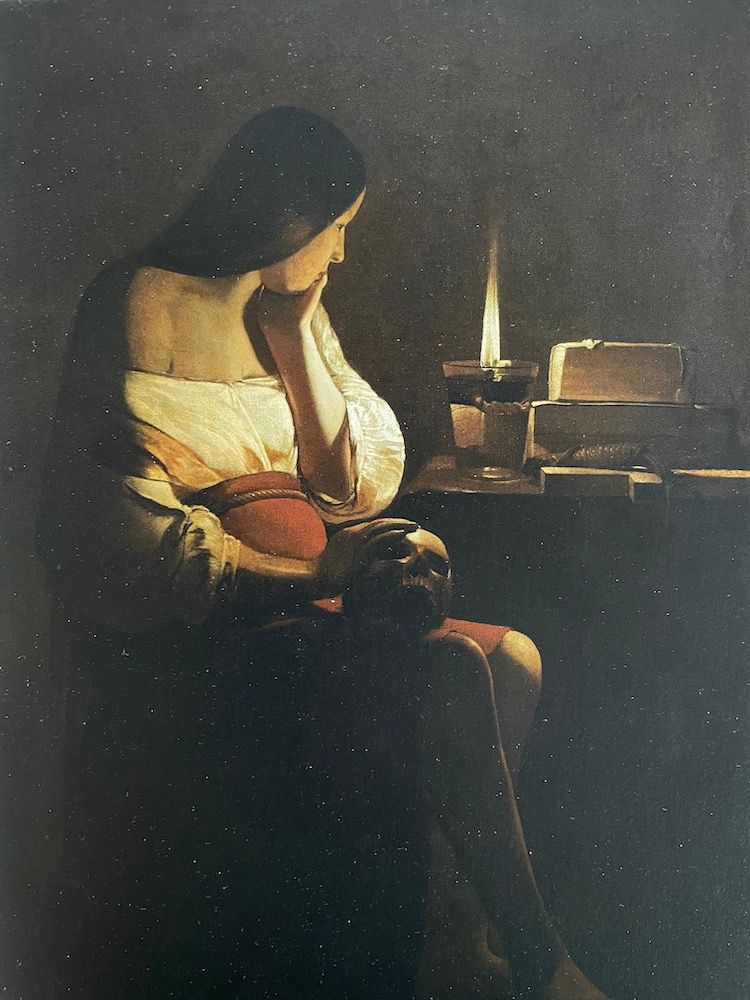

...or Georges de la Tour's Magdalene the Smoking Flame (circa 1642)...

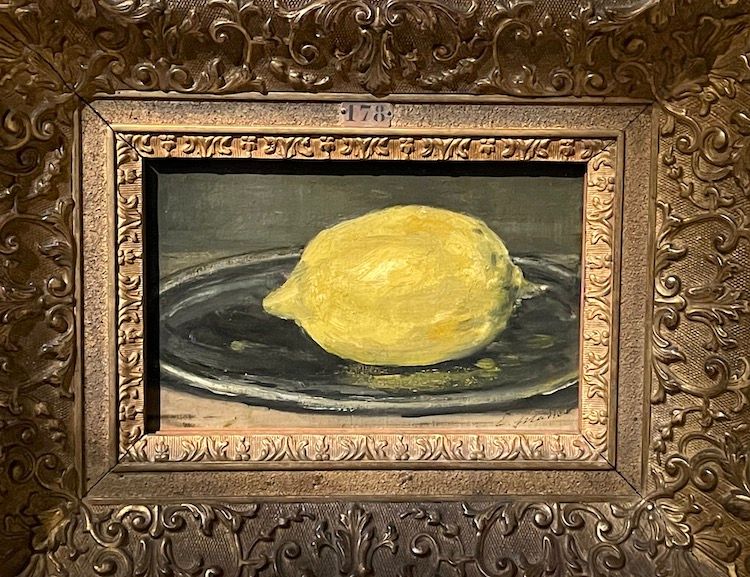

...or any of Manet's glorious depictions of humble fruit and veg, such as this lemon painted three years before his death.

I could go on and on.

As the curator Laurence Bertrand Dorléac writes, things are important to humans because we share the planet with them. And they are not in fact 'lifeless' but have their own intrinsic character and value. Things hold a host of associations and symbolisms, provide an anchor to memory and therefore mean much more to us than the sum of their often insignificant parts. I could write a short story, for example, around each small item on my desk in the top photo.

I'd even posit that things have a voice of their own. What could be more natural, then, than for humans to help give expression to that voice?

Meandering through Les Choses was like a mind-expanding trip through my own head. Revisiting already beloved works, discovering so many others for the first time, then experiencing their inventive juxtaposition, was pure joy. By the exit, I felt smarter and wiser. And quite at peace with my Thing thing.

Wishing you all a happy festive season, avec plein de bonnes choses.

___________________

You can visit my website here and if you like my photos of Things, there are LOTS more on my Instagram account here