Deconstruction

Friday, 4 June

The last couple of months, we have been attentive observers at an archaeological dig. Or so it has often seemed, since the re-haul of our old house got underway early April.

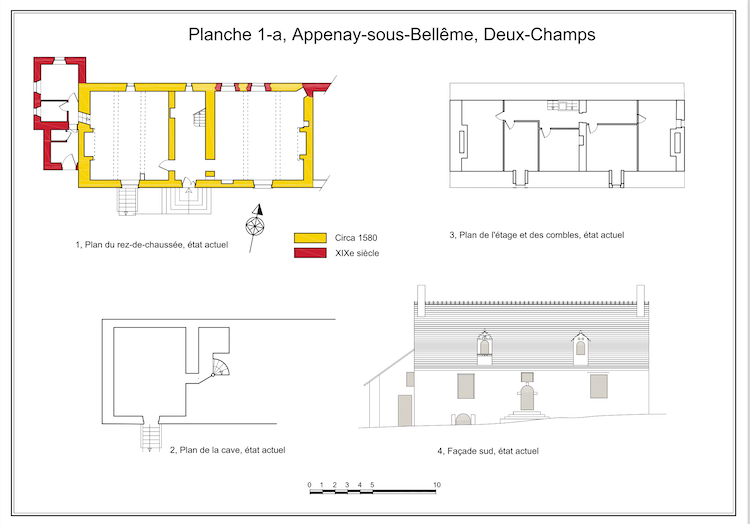

Part One of our renovation project in the Perche transformed a 19th century barn into living space for humans; Part Two aims to bring the late 16th century seigneurie now connected to it into the 21st. Here is how an architect specialising in Perche monuments historiques imagined the c.1588 plan:

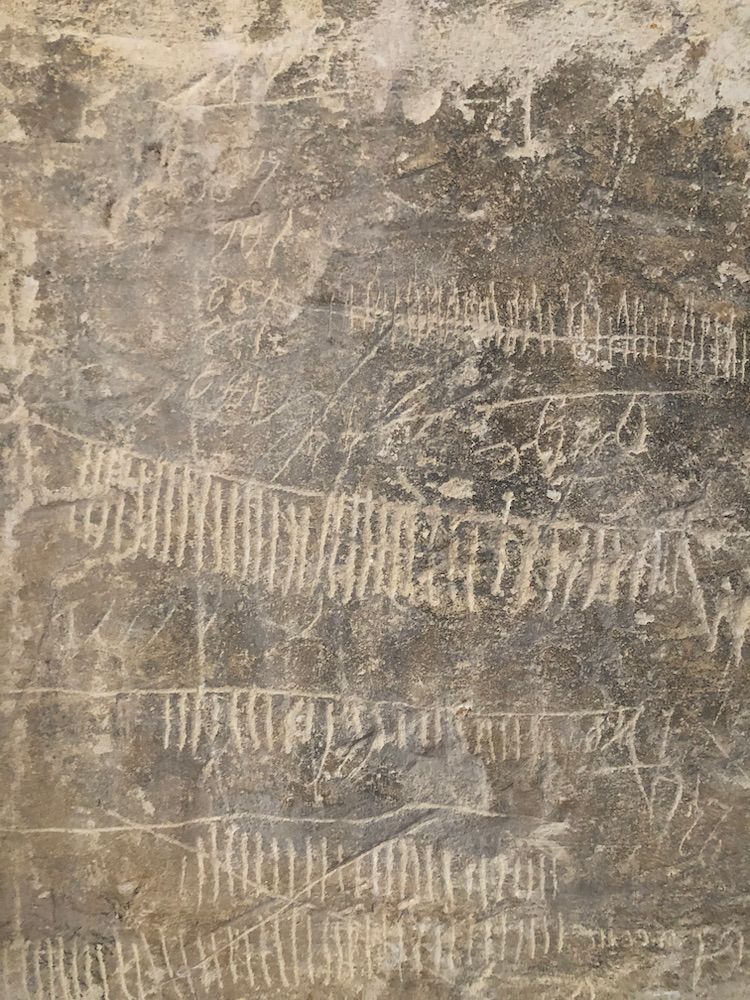

The tower you see to the right may not have existed (it is not shown on any of the early property register drawings), but the rest must be accurate because–except for the unconscionable removal of the spiral stone staircase, traces of which remain in the cellar–it's largely unchanged: an entry hall with a large sitting room to the right and a large kitchen-dining room to the left. Upstairs was originally a dovecote and later probably used for storing hay, though no one has been able to explain to me how the runic scratchings all over the door jamb fit into the picture.

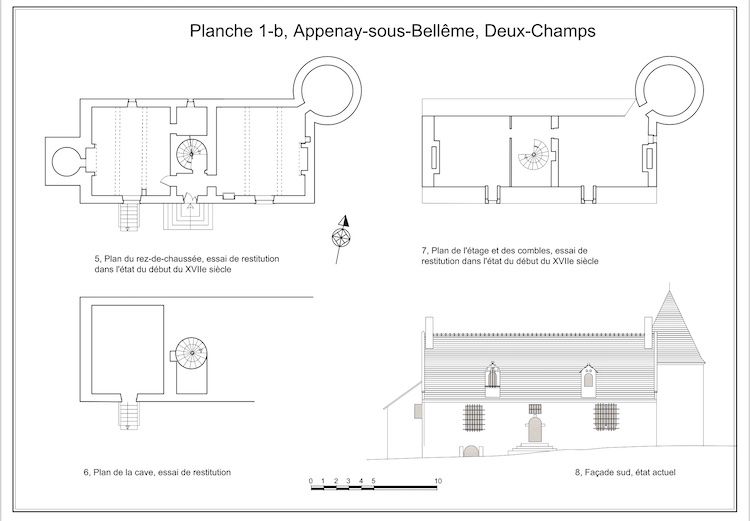

Here’s his plan of the house that we bought:

The 19th century changes are marked in red: a couple of windows were added in the living room (the harsh-weather north-face would not have had any in 1588) and the arch to the 'tower' (quite possibly merely a humble latrine) was closed. A storage and furnace room replaced the bread oven behind the kitchen chimney. Upstairs, four small bedrooms and a bathroom were created, probably early 1980s.

Having commissioned a history of the house, we know quite a lot of its story. But deconstruction can still hold surprises.

The team of masons who so exquisitely metamorphosed the barn began to...

...upstairs, so the space can be remodelled into two bedrooms with baths. In pulling up the motley collection of flooring—some parquet here, some tiles there, wall-to-wall carpeting covering the bedrooms—they discovered that the floor had been elevated about 50 cm (20 inches) above the original.

Initially, our architect told us, the massive crossbeams would have stuck up like horse jumps along the tiled surface. The heightened floor would have been added when the space was revamped for human habitation.

Once the masons tore down the dry wall and the space began to resemble its first iteration, the house seemed to drift back in time. I could almost hear a pigeon cooing, see a farmer stepping over a beam to fork some hay. But it was when they got started removing the 20th century 'improvements' downstairs that the house's soul really felt released.

Post-Second World War, it was all the rage in France to cover up old stone (I won’t venture into the psychology of what that might say about the country's dubious conduct during the German Occupation) with newly minted material. Many houses–our former country house being a good example–had a plaster mix called crépi slapped on the exteriors. It was meant to protect from bad weather, but subsequent cracks often trapped rain and created more humidity. In any case, the treatment renders textured surfaces monotone and lifeless, and we removed as much of it as we could from our old mill house in the Eure. Here at Deux Champs the outside stone was spared, but inside some previous owner (the one who removed the stone staircase, I'd bet) smothered the walls of the entry hall and kitchen-dining room with a layer of cement thick as an overly iced cake, finishing off their work with curves I guess meant as aesthetic flourish.

Drilling the stuff off took three men several weeks.

Late afternoon, after they’d gone home, David and I would wander the rooms, examining their progress and admiring their work.

The liberated stone revealed quite a lot about the ur-house. In the above photo, top left over the stairs, you can see the lintel of the former opening between the entry and the living room, as imagined in the original plan. To the left of the stairs, a cupboard emerged, with indentations still in the stone where the shelves would have been slotted.

Next to that, in an alcove where we hung our coats, the masons uncovered a bricked-in door, also evident on the original plan, but who knew what shape it would be in once the cement and bricks were removed. The masons kept us in suspense, leaving it until last on the kitchen side...

We watched them honing in on it, closer...

...and closer...until...

"Inespéré," said our architect. Besides being a work of art, it lights and lightens up the kitchen, lets the back part of the house breathe.

This project of ours is hardly Pompeii, but scraping away at what befell it during the 20th century has rivalled Netflix for us as entertainment during this most recent Covid confinement. It's also increased our sense of wonder and joy at the beauty and resilience of this old, old house down here at the end of the lane.