Plus ça change

Friday, 13 December

Some words and expressions capture a concept so aptly they are untranslatable. Often that's because the meaning conveys a quality firmly grounded in the native culture. Gemütlich for example captures the homey cosiness that Germans need to get through winter, while plus ça change, used in English as well as French to denote history being doomed to repeat itself, is anchored in the Gallic soul.

This turn of phrase has never seemed so apposite here in Paris as right now. In December 1995 France was paralysed by national transit strikes and here we go again this December for exactly the same reason: the government has proposed reforms of the pension system and the public is furiously opposed. At the heart of the debate 24 years ago was the régimes spéciaux whereby French train drivers were allowed to retire at the tender age of 50; those drivers are on the front line again today.

By a mini-twist of fate, the first section of my recently published novel The Art of Regret is set during that 1995 protest movement and provides proof in black and white of this Groundhog Day moment in French life. The protagonist Trevor talks about the entire public sector being unhappy but: “The shrillest cries [came] from the train drivers, the ones who had gained the right to retire at fifty, in the days when driving a train was hard work, not merely a matter of pushing buttons. Technology had changed, but not the laws or the drivers’ expectations.”

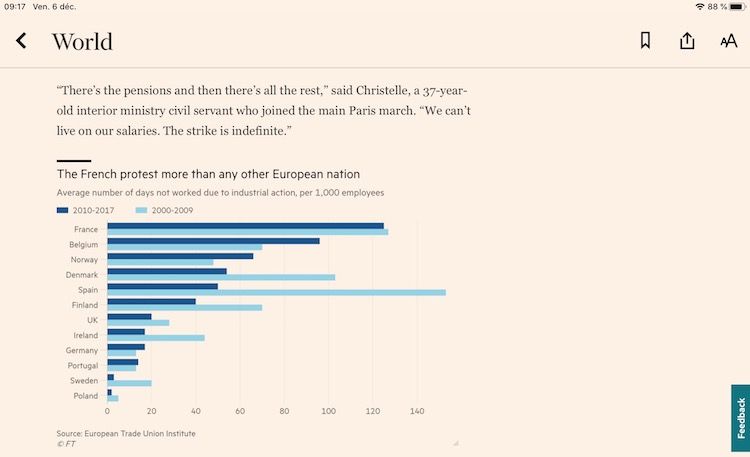

In part the French just like a good strike more than your average European.

But the causes go deeper than a penchant for revolution. Both then and now what underpins the grievances of the public sector, including teachers and hospital workers, and what garners the support of the population at large is what many French perceive to be the great divide between the elites and rest of the country. As Trevor’s French step-father Edmond says during a heated discussion at a Sunday family lunch:

“’The point is…change in France always occurs through conflict…In many ways, nothing has changed since well before Louis the sixteenth lost his head. The titles have evolved, but the dynamic has remained the same: instead of a king, we have a regal president. Instead of a ruling aristocracy in the king’s court, we have bureaucrats, the highest achievers in the country, running the place. And meanwhile, the people form their own impenetrable factions.’”

Which translates into Paris once again looking like an anthill that has been poked with a large stick. All the people who are usually travelling underground have surfaced. Streets are blocked solid with cars or police vehicles...

or eerily emptied...

There is a sense that no matter the content of the prime minister Edouard Philippe's proposed reform to simplify and equalize the 42 existing pension schemes, the strikers will keep striking until the government caves in completely, à la 1995, or until public support plummets (which may yet happen if they carry out their threat to keep going through Christmas).

Despite the appearance of one strike duplicating another, there are of course differences. Even in the film Groundhog Day, where Bill Murray keeps waking to the same morning, what happens in the course of his day varies.

This one seems to me anyway less disruptive. Some trains and buses are running and today people have other forms of locomotion. In 1995, for example, almost no one (yours truly being one of the exceptions) owned a bicycle. As such the strike actually proved a windfall to my protagonist, bicycle-shop owner Trevor: in those three weeks “the status of bicycles rose from the untouchable world of shabby hippies and the fractious proletariat to the heady heights of latest Paris chic.” The strikes launched a movement.

Certainly there were none of the electronic trottinettes (scooters) for people to glide around the city on, heedless of any pedestrians in their path. And the internet was only nascent; working remotely from home was years away. As I remember it in 1995, all activity ground to a halt. But here, last Tuesday, the scaffolding that has been blocking passage on the rue de Solférino for years, was finally being dismantled, even while a wave of protestors flowed by on their way to the National Assembly.

On the tail of the above protestors who had just walked through the Tuileries gardens were the bobos, obliviously exercising.

If everyday life seems to be carrying on with less disruption than 24 years ago, these strikes are more troubling on a deeper level. The have/have-not divide is wider than ever. There are more homeless in the streets.

If the unions are much reduced and wield less power, France has already been battered for the last year by les gilets jaunes, a more amorphous but equally energetic movement of popular discontent.

Attitudes have changed. Though no one would have accused the 1995 prime minister Alain Juppé of modesty, his arrogance was of a different brand than what President Emmanuel Macron and his cohorts are denounced for. Our wine merchant, who has been sleeping night after night at the back of his shop and, like many small business people, actually supports the reforms themselves said to me: “They always seem to have a little smile at the corner of their lips, as if they find all this mildly amusing.”

People see a smug Rothschild banker in the president's mien and do not like the face of Anglo-Saxon style capitalism. “Of course the system has to change," a friend said to me. "But not like this. Not towards a society where nothing but money matters.”

The spectre of the extreme right wing National Front looms large. With the traditional parties currently moribund, the Rassemblement National as the FN is now known constitutes, de facto, the opposition. Behind people's frustration is a belief that it’s all leading to a victory for their intolerant, xenophobic vision in the 2022 presidential elections. It's expressed with a disturbing sense of fatality, perhaps even Schadenfreude vis-à-vis the current government.

An escape into fiction is not a bad idea. In The Art of Regret you'll get a glimpse of Paris both then and now. And while you're at it this holiday season, why not order copies for family and friends as well?